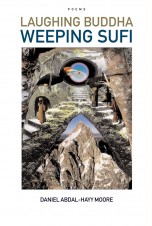

Laughing Buddha Weeping Sufi

“Excess of sorrow laughs. Excess of joy weeps.”(William Blake) A cooly impassioned, and “pathward” adventurous series of poems…

Someone asked a Zen Master, “What is Buddha nature?” and the master put his shoes on his head. Mulla Nasruddin lost his keys one night, and was looking for them under a street lamp. Someone asked him why he was looking for them there, since he’d said he lost them somewhere else. “Because here at least there’s some light to see by!”

Do we live in an Age of Reason, or an age like most others, filled with both reason and unreason, joy and tragedy, teaching of The Way (never mind for now which one) and resistance to the teaching? Human nature is a constant battlefield of dichotomies and reconciliations.

I first tasted real spiritual centering with Sensei Shunryu Suzuki, a great saintly Zen Master, in San Francisco in the early 1960s. He was a model of enlightenment. Always maintaining spiritual poise, light and easily inspired to a gentle laughter by whatever foible or sweetness was available to the world or his mind, but also deep and profound in his compassionate earnestness for our welfare and for the full “accomplishment” of our Zen practice. Muslims occasionally express a reluctance about Buddhists because of their often professed disbelief in a single Divine God. But in one talk Suzuki gave he said that Buddhists don’t disbelieve in God, they simply don’t talk about it. Yet I always found their sutras and treatises to be filled with that exalted dimension I might now call “God-consciousness.” And the proof positive of their spirituality, really, was in the radiance of their actions and in their caring for each other and the minute details of life with a real reverence that can only come from true spiritual teaching. Their “theism” is reflected more in their equanimity and openness, and their sense of a flexible immediacy to whatever the universe confronts them with.

Then when I became a Muslim in 1969 in Berkeley, California, I simultaneously entered a Sufi Tariqa whose Master, Sayyedina Shaykh Muhammd ibn al-Habib, lived in Meknes, Morocco. When I sat in his presence, may Allah be pleased with him, I was in the shadow of a giant mountain of light, an overflowing of that God consciousness, a manifestation of Allah’s Mercy, Compassion and Knowledge in human form, whose very proximity brought both tranquility and a sudden soul’s awakening, a deeper alertness. And his disciples were people who had been with him most of their lives, for he was over 100 years old, and some of them were grandchildren of his first disciples, and they also partook of that sweetness and that delicacy of being that is also stronger than the trunks of redwood trees and more resilient than any flood of social or personal tragedy. These people saw Allah’s manifestation in everything, which in its way is not that distant from seeing the Buddha-nature in everything. Each is a way of being truly human in a transparent world of signs and meanings. But Allah is the Judge.

But there are those who actually compare the ways of Taoist and Zen mystics and poets with those of Sufism, and recently the American shaykh, Hamza Yusuf, has written, “Both the Maliki and Hanafi schools have traditionally accepted jizya and dhimmi status from Hindus and Buddhists, as both religions possess Books as the foundation of their religions and retain cosmologies so sophisticated as to instill respect and study in the west…” * A recent title from Harvard University is, The Dao of Muhammad: A Cultural History of Muslims in Late Imperial China.

When these poems began insisting themselves in my frequent night vigils, I was struck by something a teacher of ours once said, that for the Buddhist enlightenment is a mental awakening, whose experience is that of a state of delighted or liberating laughter, a Satori experience of spacious detachment. While for a Sufi, enlightenment is more a bursting of the heart, a total effacement in Allah, whose expression is more often tears, of ecstasy as well as, later, of grief over separation from that epiphany and a recognition of one’s momentous shortcomings before God. This is not to say that the Buddhist enlightenment is not of the heart, nor that of the Sufi not also of the intellect. But generally speaking, the Buddhist laughs, the Sufi weeps: for both, that is the apex moment of the world.

Am I advocating a similarity of Paths between Buddhism and Islam? I’ve been a Muslim now for thirty-five years, and for me God’s statement in the Qur’an that Islam (or “submission to Divine Reality”) is the final revelation to mankind has made universal sense, in spite of modern betrayals by misguided Muslims. But we must have mutual respect and honor every worthy Path, and be supportive of any true and noble Way that leads people to stronger, sweeter, more peaceful and enlightened lives.

So Laughing Buddha and Weeping Sufi, the two protagonists of these poems set in a certain shifting and watery landscape of remembrance and imaginal realities, are not that dissimilar to the characters in Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett, except that they’re not waiting. They’re there. And they’re not strictly a dichotomy, but perhaps two sides of a single soul. It is said of the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, that he was the most laughing of men. And the Buddha? Somber and sober, laconic in his teaching to the point of silence.

A Sufi friend wrote to me recently of a trip he made to the desert of Morocco to visit a true living saint: “I was struck by how, as he poured forth prayers and blessings to us individually and collectively, the things he said were said in a voice that made me think at first he was weeping until I saw that it was actually laughter but sounded like weeping. And I remember thinking at the time that perhaps this was it, this was the fruit of the way reduced to its essence: this endless outpouring of prayers and blessings and thanks and remembrance flowing forth on a wave of laughter and tears.”

And that same friend alerted me to a verse (ayat: sign) from the Qur’an (53:42) that seems to sum it up best: That it is He who brings about both laughter and tears.

I pray that the various activities and “conversations” of Laughing Buddha and Weeping Sufi will bring the taste of this particular landscape to the reader as well.

_________

Note: when I went to give these poems titles (I had been numbering them in their notebook) I was inspired to dash out a title without looking at the poem first, so the titles are actually independent of the poems, “chance” titles” as sit were, slightly goofy Haikus that are either in harmony or at odds with their subsequent poem.

*(Seasons, Spring -Summer, 2005)

Categories: Author's Introductions